Writing correct software is hard. Whether you’re using functional programming or finite state machines, understanding the problem you’re solving and understanding your code are both required for correctness. Async functions and generators are stateful syntax for which we can draw state diagrams so that we can understand them. If you know how to break your problem down into a finite state machine then this will show you one way of implementing it as well. Deciding whether doing so would be ergonomic for you and meet your requirements is something you will hopefully be able to do by the end. If it wouldn’t be then maybe you’ll see a path that would make it viable.

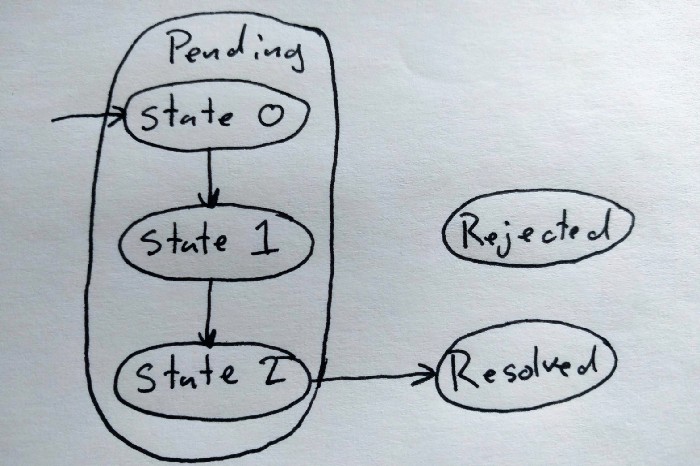

A finite state machine has different states that it transitions between and it can only be in one state at a time. A Promise has three possible states: pending, resolved, and rejected. For finite state machines we can draw a state diagram that has circles for the states and arrows describing transitions between those states. A state diagram for a Promise would look like this:

The arrow into the Pending state tells us that this is the initial state. What makes a promise a promise is conforming to the promise protocol, you can find it here: https://promisesaplus.com/. In short, a promise has a then method that registers callbacks for when the promise either resolves or rejects. The await keyword calls that then method under the hood so if you want to make something await-able, you need to have a valid then method. Or at least valid enough — await doesn’t care if your then method returns a promise.

Back to the point, let’s look at a simple async function:

function delay(ms) {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms));

}

async function Example1() {

console.log('Transition 1');

await delay(1000); // State 1

console.log('Transition 2');

await delay('1000'); // State 2

console.log('Transition 3');

}If we draw a state diagram for this code we would get this:

Here’s the recipe for constructing the state diagram for an async function:

-

Every async function’s state diagram starts with three states: State 0,

Resolved, and Rejected.

Since Promises run in a microtask there is a little bit of time between the async function being called (creating the promise) and the start of it’s code running.(Promises actually run eagerly, so there is no state 0. I misunderstood the difference between methods registered with then which are always called asyncronously using microtasks and the promise code itself. I apologize.)

This last step shows us that we can have a state-machine within another state-machine. Our async function is running within a Promise. Sub state machines are the basis for managing complexity in our state machines. As a system grows in complexity you can start grouping states implemented in other async functions. You may also find that two machines should actually run in parallel. Managing those is often where you will want to use the Promise combinators (https://v8.dev/features/promise-combinators). Here’s an example that uses the Promise.all combinator:

function getImage(url) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const image = new Image();

image.onload = resolve.bind(image);

image.onerror = reject;

image.src = url;

});

}

async function Example2() {

const imageList = await fetch('url').then(response => response.json());

const convertedImages = await Promise.all(imageList.map(async imageUrl => {

const image = await getImage(imageUrl);

const result = await makeGrayscale(image);

return result;

}));

return convertedImages;

}And its state diagram:

Each of the sub state machines operate in parallel. The fetch and JSON conversion could fail resulting in rejecting from the image list fetching state. The image not being able to load can also result in a rejection from the sub async function. As you can see, the resolved and rejected states often feed into one another. Also, Promise.all will reject if any of the sub promises reject but without promise cancellation, the rest of the images would still finish. Promises don’t give you a way to avoid that extra work.

DOM Nodes are finite state machines that predate Promises and in the coming era of custom-elements and more fundamental browser APIs I think it’s important to show that a state machine pattern or library can communicate well with its surroundings. To do that for async functions, we’ll need to convert anything that would normally interact via callback into something that is then-able. You’ve already seen this process in the delay function from the first example. Next we’ll need to have a good way of reacting to property changes easily. Lastly, we’ll want to switch from yield to using the browser’s native language for conveying state transitions: events.

First is listening to outside events. This is a fairly simple process. You may be able to think of a better way of doing this but here’s my implementation:

function listenOnce(el, event) {

return new Promise(resolve => el.addEventListener(event, resolve, {once: true}));

}

async function* listen(el, event) {

const differed = {

callbacks: [],

resolve(value) {

this.callbacks.forEach(func => func(value));

this.callbacks.length = 0;

},

then(callback) {

this.callbacks.push(callback);

}

};

const handler = e => {

differed.resolve(e);

}

try {

el.addEventListener(event, handler);

while(1) {

yield await differed;

}

} finally {

el.removeEventListener(event, handler);

}

}You can see my not quite conforming differed implementation above. These two functions will let you either await a single event being fired (a button click for example) or iterating over multiple events (perhaps the input event on an input element).

What about properties? I was doing some Android development and learned about the LiveData class which is fairly easy to implement in JavaScript.

class LiveData {

constructor() {

this.waiters = [];

}

set value(newValue) {

this._value = newValue;

for (const callback of this.waiters) {

callback(newValue);

}

this.waiters.length = 0;

}

get value() {

return this._value;

}

then(callback) {

this.waiters.push(callback);

}

async *[Symbol.asyncIterator]() {

while (true) {

const lastIssued = this._value;

yield lastIssued;

if (this._value == lastIssued) {

// If we're caught up then wait for an update

await this;

}

}

}

}This class let’s you iterate over a value that can change. It makes sure that you have the most up to date value even if you don’t request the next value immediately. To make it back into a property would take a setter / getter pair on the object that you want the property on.

Issuing events is easy enough using CustomEvents. The Mozilla Developer Network has lots of information on doing that and I don’t think there’s any tricks to it

There’s one kind of input that isn’t easy to make async: abort or cancellation. There is no promise cancellation. Cancellation can initiate from many different places whether it’s the disconnected callback on a custom element or a cancel method that you want to build into your state machine. Any time we use the await keyword we are going under until it resolves or rejects so if that promise doesn’t take into account cancellation, then we aren’t taking into account cancellation.

EDIT: The new method of handling this — as standardized for use with the fetch api — is using an AbortController and paired AbortSignal. The promise from a fetch request that is aborted throws an AbortError. If your operation can be aborted, then you need to accept an AbortSignal. If you operate on any cancelable sub-operations, you can just pass that signal down to them. They should throw an AbortError waking you back up. If you are waiting on a non-abortable promise then you’ll have trouble. One method of getting around that is to wrap the promise that doesn’t abort in one that will abort when the signal issues the abort event. I’ve made my own version that I called wrap-signal As always, concurrency is a complicated problem that introduces many different failure modes. Handling all of those without strong type enforcement is difficult. AbortController seems to be the direction that the language is going so it’s good to get ready for it.

What this means is that if you need something that is cancelable, you either have to be really careful and use something like Promise.race with your cancel differed and then do some cleanup perhaps using the AbortController or you can use something that can be cancelled: generators. Iterators have a return method which when implemented by a generator acts as though the statement after the previous yield was a return statement. The only code that can run after a return statement is a finally block. If you’re writing an async generator then the return function will only take effect at the next yield so you have to keep yielding to check if you’ve been cancelled. To make it fully cancelable we can’t use await which means sticking to a normal generator. To then make it async we can yield the promise we would have awaited and then the caller has to call next with the value that the promise resolved with or call throw if the promise threw an error. I’ll show you my implementation for a simple cancelable setup. You can find another example of this technique (it does a slightly different thing) in Cancellable Async Functions in JavaScript

function cancelable(instance) {

const result = (async () => {

let step = instance.next();

while(1) {

const {value, done} = step;

if (done) {

return value;

} else {

try {

const result = await value;

step = instance.next(result);

} catch(err) {

step = instance.throw(err);

}

}

}

})();

result.cancel = () => instance.return();

return result;

}What this is doing is taking an iterator that yields promises (the ones that it otherwise would have awaited) and then awaits the promises for the generator feeding the result back in later (including errors that might be thrown by the promise).

EDIT: This is also similar to Bluebird coroutines which I didn’t know about at the time.

You might use it like this:

function* testHelper() {

console.log('Entering Helper');

yield delay(1000); // State H-1

console.log('Helper: Transition 1');

yield delay(1000); // State H-2

console.log('Helper: Transition 2');

return 5;

}

function* test() {

try {

console.log('About to call testHelper');

const value = yield* testHelper(); // State T-1

console.log(`Got ${value} from testHelper`);

} finally {

console.log('starting the finally');

yield delay(1000); // State T-2

console.log('finishing the finally');

}

return 'success';

}

const a = cancelable(test());

a.then(result => console.log('cancelable resolved with', result));

// a.cancel() to cancel the machine at any timeThinking about this approach, it’s quite like the Futures implementation in Rust. In Rust a Future is polled and when it can no longer proceed it makes sure that something will tell the runtime to wake up the future by polling it again. In our case, the runtime is the cancellable and when the promise resolves it knows that it can resume that generator. This takes care of the cancellability problem and as you can see, you can even have async code in the finally block meaning that you can do async tasks during cleanup.

Let’s also draw the state diagram for this setup:

I’ve used dashed lines to indicate that a state isn’t actually asyncronous (it is just passed through during a transition). With generators, everything except the yield statements are part of a transition. There’s no state 0 either since next will run the generator synchronously instead of as a microtask.

We all have state somewhere and if it’s not represented in the code pointer of an async function or a generator then it’s probably on an object somewhere. If you would like an argument for why using finite state machines instead of such state properties might be a good idea, I’d recommend the introduction of this video.

My goal in explaining this use of async functions and generators had been to advocate for using them to describe any systems you thought might be finite state machines. In my testing I’ve found it clear, concise, and usually pretty understandable. Writing an async function feels like telling the story of a system’s behavior. I think that these benefits come from the life-cycle provided by generators and the naturalness that comes from using normal control flow syntax for defining state transitions. But if it’s an async generator then that life-cycle doesn’t include cancelability during an await which is a big problem and really holds them back. I don’t think that async generators will be the right tool to describe all state machines like I had supposed when I started.

Custom elements represent a new level of reusability that we need to steward with reliable and maintainable code. I believe that finite state machines are a performant way to achieve reliability and I think that finding patterns for using the built-in language features to build those state machines will make code that’s maintainable. I think that those patterns will involve some combination of async functions, generators, and async generators — probably nestled in a library that manages canceling and other orchestration. I look forward to watching that be built — or whatever even better thing the community finds — as time goes on.

Thanks for reading, let me know what you think.